How Sanskrit Literature Reclaimed 'Alternative' voices from Panchtantra to Hitopadesha

Explore Sanskrit literature's unique perspective on animals and society with insights from Panchatantra to Hitopadesha. Uncover non-human voices and societal critique.on Dec 06, 2023

Animals in the Hitopadesha are more than just metaphors for people, according to scholar Shonaleeka Kaul during a lecture in Delhi.

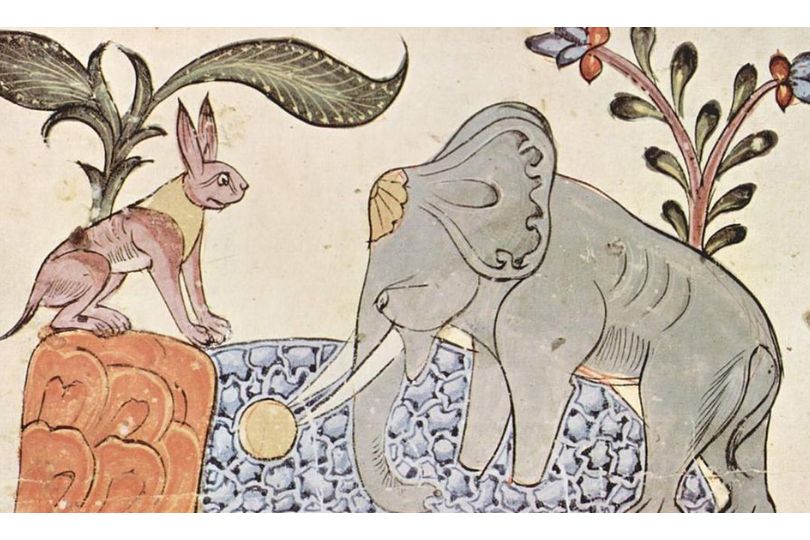

A devoted pet mongoose saves a baby from a snake only to be stung by his owner. A donkey is thrashed for complaining about a robber. A chatty turtle on a stick falls to the ground when he opens his lips. These Panchatantra fables, which every Indian child has grown up with, are more than just light-hearted entertainment; they shed light on historical human-animal connections and dig into 'niti,' or government and morals.

"The animal voice and perspective is central to these stories, often displacing the human voice," said historian Shonaleeka Kaul at the India International Centre in Delhi during a presentation on the Panchatantra-Hitopadesha tradition.

Kaul, a history professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), stated that the Hitopadesha stories call into question the standard notion of animal representation in literature. They challenge the idea that animals are simply symbols for humans and their experiences.

The Panchatantra, a collection of Sanskrit fables from the third century BCE, is supposed to have been the inspiration for the Hitopadesha, which was composed much later, in the 12th century BCE.

"Animals in the Hitopadesha are not just metaphors for humans; they are very much beings in their own right with their own values and actions," she went on to say.

A rebellious language

The removal of humans from the core of the story demonstrates that Sanskrit literature was invested in recovering other voices, including non-urban, non-elite, and non-human voices. By reading these writings and their animal representations, we "renegotiate our understanding of Sanskrit," according to Kaul.

She then cited the film The Snake And The Mongoose, in which the human is represented as careless and the animal as faithful. In this story, the woman accidentally kills her pet mongoose because she believes he is a threat to her child rather than the snake.

The human voice is secondary in The Donkey And The Thief, which concentrates on animal communication.

Kaul also provided examples of Hitopadesha stories that demonstrate an understanding of societal hierarchies, caste hierarchy, and the agency of women. The narrative of the mongoose, which includes a Brahmin couple, is not afraid to show them in the wrong.

Despite the language's exclusive use by Brahmins and other 'higher' castes, Kaul contended that Sanskrit literature courageously questioned the established status quo. Through the representation of animal voices and lives, it grasped and satirised society order and hierarchy.

"We believe that just because something is provocative, it must be said by women or people who are marginalised." However, Sanskrit literature such as the Hitopadesha demonstrates that this is not the case."

Hitopadesha is a 'delightful shastra'

Kaul went on to explain how animals in the Hitopadesha altered how life lessons were taught. The shastra (old text) was more than merely theoretical; it was grounded in actuality.

Some stories taught lessons as simple as "learn when to keep your mouth shut" or "don't interfere in what doesn't concern you."

"The Hitopadesha is, therefore, a shastra, but it is a manoharam shastra — a delightful shastra that teaches you about real life," Kaul added.

Most fables either utilise animals to teach people a lesson or use humans as stand-ins. Animal stories are rarely told from and by the animals themselves without devolving into fantasy tales.

An inquisitive audience member asked Kaul near the end of the talk if her interest was on animal history in early India or on Sanskrit literature. She claims that the two are inextricably related. It is impossible to analyse animal history in ancient India without first comprehending Sanskrit literature and its proponents. At the same time, animal imagery in the Hitopadesha adds to and improves knowledge of Sanskrit literature.

"As a historian, I cannot choose between medium and content because you cannot talk about one without the other."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.